How can we help keep kids in school in Latin America?

3 Tips to Reduce School Dropout Rates

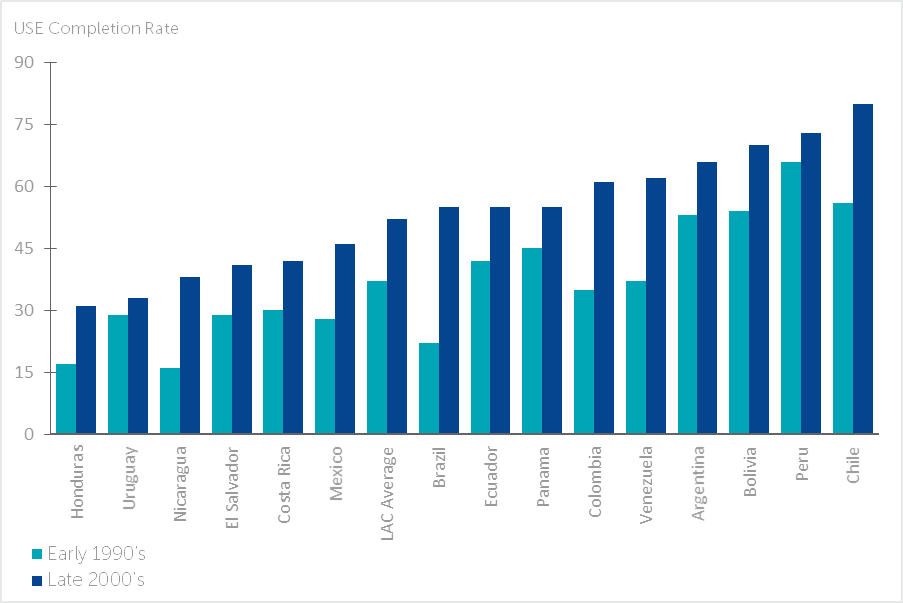

Despite having made impressive gains in primary and secondary school enrollment over the last few decades, countries in Latin America and the Caribbean have struggled to ensure that all children complete secondary school. Although there are clear links between secondary school completion, individual wellbeing, and national economic prosperity, only 59 percent of youth in the region complete this level of education.

Upper secondary education completion rates in Latin America, early 1990s and late 2000s

With the economic and social importance of students reaching this milestone in mind, R4D, in partnership with CAF – Development Bank of Latin America, recently completed a study identifying principles for reducing the incidence of secondary school dropout. This study, which featured in-depth case studies of four promising dropout-reduction programs in Chile and Mexico, sought to examine how contextual, institutional, and programmatic factors contribute to the successes and challenges faced by dropout reduction strategies.

Over the course of our research, we found that isolated programs are insufficient to adequately address the multitude of factors that push and pull students out of school and are unable to singlehandedly transform schools into places where students wish to remain. Instead, any response to secondary school dropout should be systemic, take place at national and local levels, and involve a reconceptualization of the roles of school staff and the needs of students.

With these principles in mind, we identified three concrete components that any school dropout strategy should incorporate.

1. Any dropout response strategy should have at its foundation strong early warning systems that operate at both national and local levels.

Every early warning system should first identify students that stand the greatest risk of dropping out, and then activate a response to provide the student with support tailored to his or her needs. National early warning systems serve to direct interventions toward the students with the highest risk of dropping out well before they reach the point of leaving school, using data on factors such as attendance, age-for-grade, behavior, and course performance. However, national systems are generally unable to nimbly respond to changes in student circumstance. Locally-operated early warning systems can complement national systems by identifying the specific challenges facing students and developing a tailored response, including engagement with parents and other community actors.

2. Strategies should invest in school-level personnel who are dedicated to reducing dropout.

All too often, policies aimed at reducing dropout provide one-off trainings or manuals, which are insufficient to create the changes necessary to ensure that children remain in school. Additionally, many programs rely on teachers for implementation, yet teachers — especially those in under-resourced schools where dropout rates are the highest — are often already overwhelmed with other activities that are given a higher priority. An effective dropout-reduction strategy includes investment in individuals at the school level who have the explicit responsibility to implement dropout-reduction activities. An alternative to hiring new personnel is to provide incentives to existing school staff to prioritize and faithfully implement dropout-reduction activities.

3. Beyond providing support to at-risk students, initiatives should take steps to improve the school environment to ensure that schools are places that students want to be.

Students that are subject to bullying or who don’t feel a sense of connection to their schools are much more likely to drop out. School staff that are insufficiently prepared to support students that face economic, social, or behavioral challenges may also inadvertently create an environment that discourages students from continuing their education. In order to address systematic challenges to student wellbeing within schools, programs should develop school improvement plans, sensitize teachers and other staff to challenges commonly faced by students, and assign one school actor the responsibility of monitoring and improving the school environment.

Encouragingly, we found plenty of reason for optimism in the experiences of Chile and Mexico — both countries have been able to sharply increase secondary school completion rates in a relatively short period of time. However, these country examples highlight that doing so requires sufficient political will and, in some instances, a substantial investment of resources. Isolated programs, however well-designed, will not do enough to address the wide range of complex factors that lead students to drop out of school. Ultimately, actors at all levels of school systems must adopt an orientation that conceptualizes dropout not as an irresponsible decision of individual students, but as a sign of weakness in the system that must be addressed.

Read the full report referenced in this study, Promoting Secondary School Retention in Latin America and the Caribbean: Lessons from Mexico and Chile, available in English and Spanish.

Photo © Monica Rodriguez